Malaysia PM Anwar makes sweeping Cabinet changes, including new trade and economy ministers

PETALING JAYA: On paper, earning RM7,000 a month as an assistant engineer should offer a comfortable life. But for Mohd Amir Izzuddin, it barely covers the essentials.

With loans and credit card debts exceeding RM150,000, more than 85% of his income is swallowed up by repayments, leaving little room for savings or unexpected expenses.

CLICK TO ENLARGE

CLICK TO ENLARGE

Not all of Mohd Amir’s debts stem from poor decisions. Raised in a village, he grew up believing that a degree and hard work would be his ticket to a modestly better life.

“We’re always told to study and work hard to live better. That’s exactly what I did. So is it really wrong for me to choose a higher-end car and a studio apartment or to enjoy a nice premium steak or seafood platter twice a month? Is life supposed to be so bland, only rewarding us when we’re too old or sick to enjoy our savings?” he said.

Mohd Amir also supports his parents, providing them with a monthly allowance to help cover their expenses and medical bills.

ALSO READ: Think before you swipe, experts tell youths

“They don’t work and have no pension. I give what I can, but it is never enough with the rising cost of living. A proper meal nowadays costs no less than RM12 and my monthly expenses for food exceed RM1,500,” he said.

Now at 35, and more than a decade into his career, Amir regrets that he’s still struggling to stay financially afloat.

“Every month is a battle with the bills. I have no choice but to rely on credit cards, personal loans and BNPL (Buy Now, Pay Later) offers to manage my expenditure since these facilities are very easily available,” he said.

The financial stress has also affected his personal life.

“I have chosen to remain single until I feel financially stable. If I had my own family, they might have to skip meals with the kind of expenses I face monthly,” he said.

Communications executive Arthur Lim, 45, learned firsthand how debt can bring heartache after watching his colleagues sink into financial trouble during his 20s.

“Loans are a huge and profitable business. Those offering them will naturally promote and entice people, but repayment is where the problem begins,” he said.

Lim pointed out that vehicle financing can be particularly costly, adding that an RM120,000 car loan repaid over nine years could result in almost RM100,000 in losses when both depreciation and interest are taken into account.

“Yet some earning under RM4,000 still take the plunge just to look cool. I’m puzzled how these loans were approved when borrowers had other commitments such as home or personal loans.

“There are unscrupulous loan agents who facilitate these huge borrowings for those with low income,” he said.

Lim said he only has a home loan which he took out a decade ago and was relieved to know that the value of his house has appreciated by almost 80%.

For A. Kevin, who is in his 30s, paying off his loans consumes nearly 90% of his RM6,500 income each month, despite his efforts to be thrifty.

He said that as a content creator, a significant portion of his income also goes toward computers, smartphones and the latest software.

“I studied hard and earned a degree, but I feel like I am living like a low-income earner,” said Kevin, adding that he was fortunate his wife’s income helps supplement the household expenditure.

Bank Negara Malaysia’s Credit Counselling and Debt Management Agency (AKPK) told The Star yesterday that credit card debt remains the main reason why most individuals struggle to keep up with their financial obligations.

Since 2006, more than 1.4 million Malaysians have approached AKPK for assistance in managing and recovering from their debts.

According to the Finance Ministry, Malaysian households owed a combined RM54.9bil in credit card and BNPL debt as of September 2025, highlighting the growing reliance on short-term and revolving credit to manage daily expenses.

The pressure has become so intense that it is now spilling over into rising bankruptcy cases.

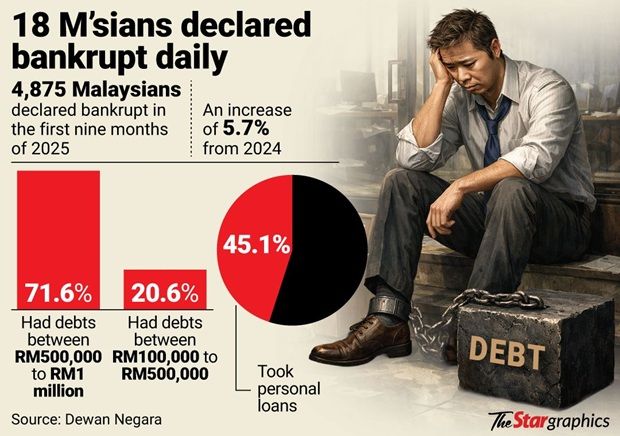

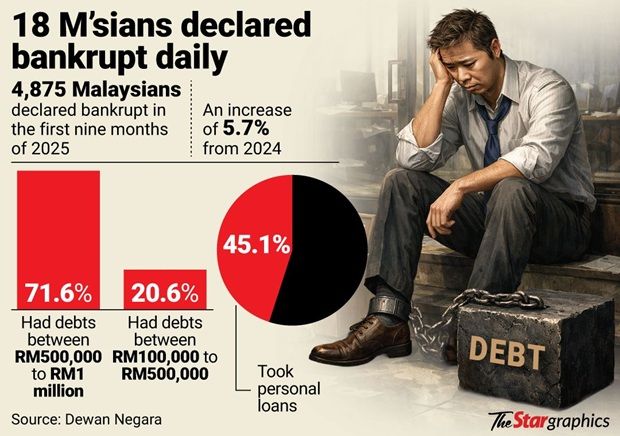

Earlier this month, during a debate on the Supply Bill 2026 at the Dewan Negara, Senator Datuk Sivaraj Chandran revealed that an average of 18 bankruptcy cases are reported daily in Malaysia, with nearly 60% involving individuals under the age of 30.

He said that between January and September 2025, a total of 4,875 Malaysians were declared bankrupt – a 5.7% increase compared to the same period in 2024.

Sivaraj was also reported to have revealed that about 71.6% of those declared bankrupt owed between RM500,000 and RM1mil, while another 20.6% carried debts of RM100,000 to RM500,000.

Contrary to common belief, it wasn’t housing or business loans, but personal loans and credit card expenses that were the main contributors – accounting for about 45.1% of bankruptcy cases.

Although many people assume that loan approvals are handed out too easily, a senior banker says the process is actually much more stringent than it appears.

Senior economist Mohd Afzanizam Abdul Rashid said that banks generally rely on the Central Credit Reference Information System (CCRIS) when assessing loan applications, paying particular attention to a borrower’s repayment behaviour over the past 12 months.

“Any arrears will reduce the applicant’s credit score, and the lower the score, the slimmer the chances of approval. At worst, the application may be rejected,” he said.

Afzanizam added that CCRIS reports also allow banks to see how many financing facilities an applicant has applied for across different banks, even if those applications haven’t been approved yet.

Existing loans that have been restructured or rescheduled are also clearly indicated in the report.

“All these factors influence the credit score,” he said. “Borrowers who are already heavily indebted face extremely low chances of securing new financing. In such cases, applying for additional credit is likely to result in outright rejection.”

Related stories: