Differentiating Between Chronological Age Vs Biological Age

OUR BIOLOGICAL AGE MIGHT NOT NECESSARILY BE THE SAME AS OUR CHRONOGICAL ADE - DRSHIRLEY KOEH:

Emagene Life & TruDiagnostic in Malaysia's first biological ...

Differentiating Between Chronological Age Vs Biological Age

If you experience fear of growing old, you are not alone. A 2014 survey shows that nearly 90% of Americans are afraid of the implications of aging, from an increased risk of disease to declining physical ability. However, this fear often stems from two assumptions: that getting old is synonymous with disease and that you have no power over the aging process. These aren’t necessarily the truth.

There’s a lot that needs to be understood about the complex process that is aging. However, since the introduction of concepts such as biological aging and aging biomarkers in 1988, science has made significant advances.

Today, we know that your true age is defined by more than the date on the calendar or the number of candles on your birthday cake. Instead, your biological age is a more accurate indicator of how old your body is, as well as of what disease risk profile you are facing at any point in life.

Unlike chronological age, biological age can be influenced and reduced with the right interventions. And, with RELATYV, you can also access a comprehensive tool to track your biological age and intervention progress in real-time. Let’s cover all you need to know below.

Understanding Chronological Age And Biological Age

American developmental biologist Scott F. Gilbert defined aging as “the time-related deterioration of the physiological functions necessary for survival and fertility.” More broadly, the term aging can be used to describe the biological processes associated with the passing of time, which lead to physical and cognitive decline. These changes, which are often permanent, affect any aspect of our body and mind, from cells and organs to the body’s own systems.

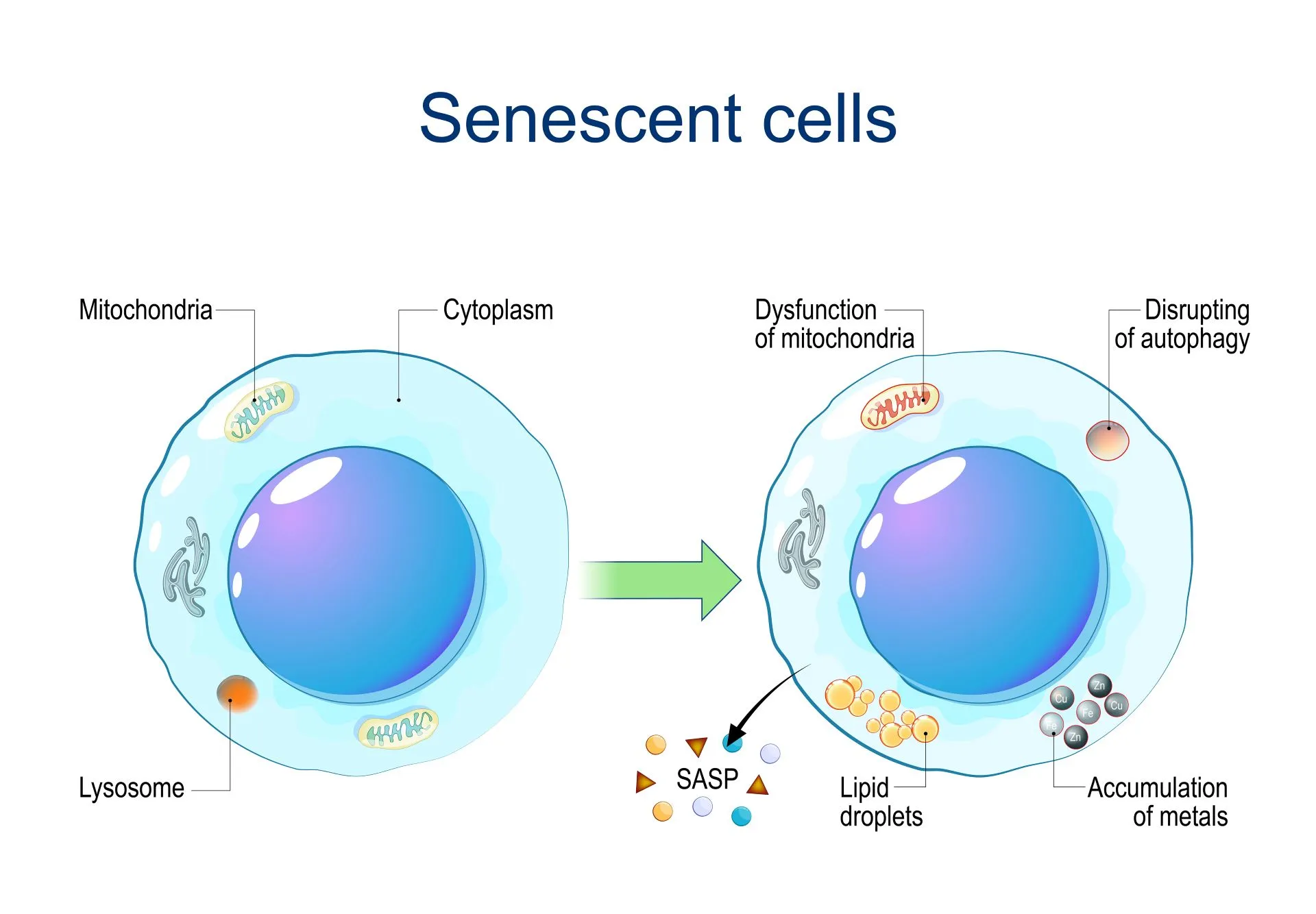

Most theories link the beginning of the aging process with cellular senescence – or, in simpler terms, cellular retirement. This occurs when the cells in our body cease to divide, often in response to different triggers, including DNA damage and dysfunction of the telomeres (the protective caps at the ends of our chromosomes).

In certain scenarios, this process is critical because it prevents damaged or stressed cells from propagating, aiding in tumor suppression and wound healing.

However, when cells stop dividing, they also stop acting as young, healthy cells – which can lead to a decline in the reserves of progenitor and stem cells, which are essential to replace damaged cells and tissues and to keep the body working properly.

Additionally, the accumulation of waste materials from older cells can begin to accumulate and kickstart diseases commonly associated with aging.

Several theories have attempted to explain why cells, at some point in our lives, stop dividing. Some, like the Hayflick Limit, suggest a sort of biological countdown. Others link the accumulation of cell byproducts (known as free radicals) or damage to the energy-producing center of the cell (mitochondria) to aging.

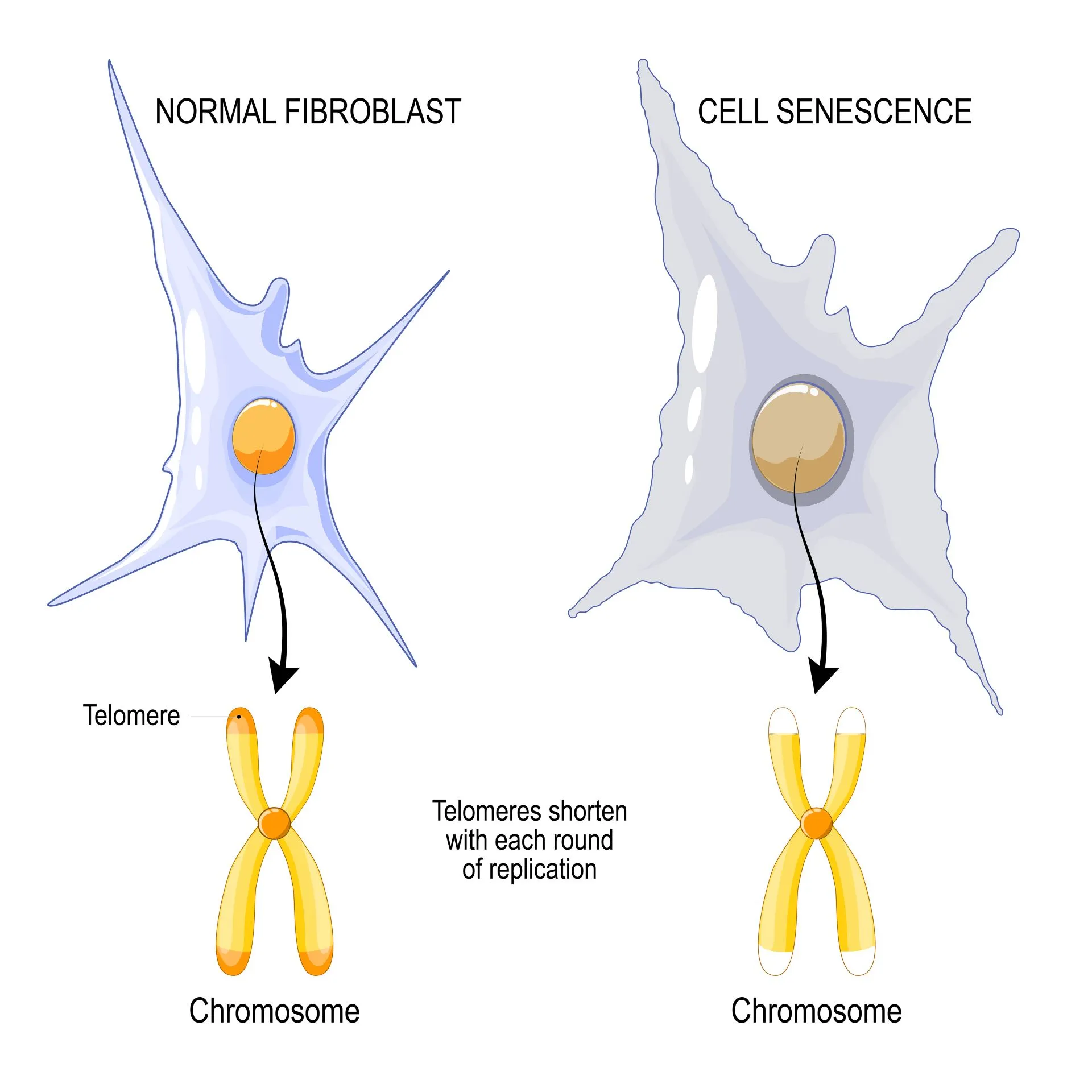

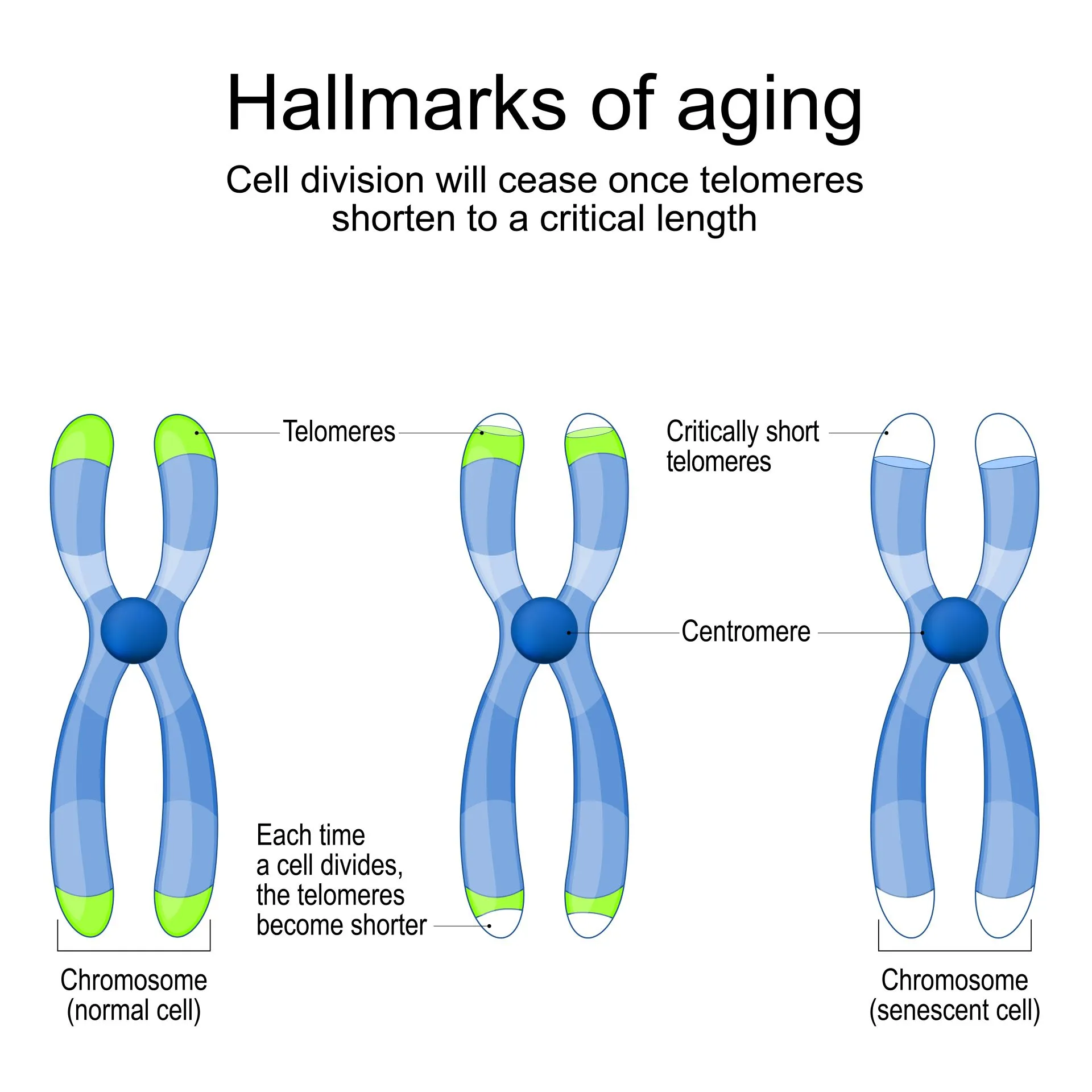

More recently, studies have begun to uncover the connection between aging and telomere shortening. Telomeres shorten at each cell division cycle. When they become too short, they can leave the chromosomes unprotected and cause genome instability, eventually leading to cellular retirement.

We’ll look at the relationship between telomere length and aging in more detail below.

Chronological age and biological age are two different measures that can be used to determine how your body is aging. Unlike chronological age – which simply tells you how much time has passed since your birth – biological age is a more accurate indicator of how old your body is, how long you can expect to live, and what your disease risk profile is. Recent research findings link biological aging with cellular retirement.

What Is Chronological Age?

Chronological age represents the exact amount of time a person or organism has existed, typically measured in units such as years, months, or days since birth. It’s a fixed, easily quantifiable measure, independent of health status, lifestyle choices, or genetic factors. In other words, you can always know how old you are based on your chronological age.

Nonetheless, while this is a useful marker of time, it doesn’t necessarily reflect biological age, which may be influenced by a multitude of factors including genetics, environmental exposure, and lifestyle habits. Unlike biological age, chronological age cannot be modified.

What Is Biological Age?

Biological age refers to how well your body functions compared to your chronological age. It is a dynamic measure of one’s health and vitality. It determines how well your body’s cells and systems are functioning and how fit you are compared to the standard for your chronological age range.

For instance, a person may be chronologically 50 years old but due to a healthy diet, regular exercise, and optimal stress management, their biological age may be measured as 40. This figure indicates that they have a health and risk disease profile akin to an average 40-year-old, showing that, biologically, they are aging at a slower rate.

Similarly, two people with the same number of birthdays can have different biological ages, depending on how they are aging internally, due to genes and lifestyle choices.

By telling you how old your body truly is compared to your chronological age, biological age also more accurately predicts your disease risk profile, lifespan, and expected healthspan (the number of years lived without chronic illness or disability).

Unlike chronological age, biological age can be modified by addressing the factors that influence this measure. These factors include:

- How well you manage stress

- How physically active you are

- Your diet

- Exposure to toxins or pollutants

- Genetics

- Habits such as smoking and drinking alcohol

- Sleeping habits

- Environmental factors, such as where you live or work

- Systemic inflammation, or low-grade, chronic inflammation that, over time, affects how your body functions. (Systemic inflammation is also considered to be the root cause of various chronic diseases, from diabetes to respiratory illnesses, metabolic dysfunction, and cardiovascular disease).

Having a “give up” mentality can also make you age faster. If you feel you’ll never be able to overcome medical conditions or improve your health, you are more likely to give up trying, which can lead to poor lifestyle choices that make you age faster.

Over time, these factors can influence the rate of cellular retirement and telomere shortening, which accelerate the biological aging process.

Understanding The Difference Between Chronological Age And Biological Age

Your chronological age simply states how many days, months, or years you’ve lived – it does not provide any information regarding how well your body’s system functions, how old you are internally, or how likely you are to develop dementia or diabetes. It is truly just a number.

On the other hand, you can think of biological age as depicting a comprehensive picture of your aging rate and body function, based on physiological evidence. According to studies, biological age can be used as a predictor of the onset of diseases associated with aging, including dementia, as well as other aging-related diseases.

How They Are Measured

Chronological age is very easy to calculate by looking at the passing of years and days – counting your biological age, on the other hand, can be more challenging and require specialized tests.

Medical diagnostics today look at a wide range of indicators that describe several aspects of how your body is aging and may predict your disease risk. These “indicators” are known as biomarkers of aging, a concept initially introduced by Sprott et al in 1988.

Over the past years, science has progressed in leaps and bounds and, today, doctors are able to use a wide range of more accurate predictors compared to the ones used in the 1980s. Thanks to advanced technologies, these indicators are also more accurately measured, offering precise estimations of a person’s biological age.

Two of the main biological markers used today to determine internal age-related changes are telomere length and DNA methylation.

- Telomere length

In simple terms, telomeres are cap-like structures at the end of our chromosomes that protect them against deterioration. They are composed of repetitive sequences of non-coding DNA that protect these chromosomes – just like the plastic tips on shoelaces protect from fraying.

With each cell division, these telomeres get shorter. Once they become too short, the cell is unable to divide and becomes senescent (goes into cell retirement) or dies. Scientists have seen that telomeres get shorter as we age (i.e. as our chronological age increases).

However, the rate at which they shorten is also determined by a wide range of factors, including lifestyle, environment, exposure to pollutants, stress, and inflammation. Because of this, telomeres are often considered to be our “biological clock.”

Over the past years, the global scientific community significantly focused on the implications of shortening telomeres. Some key research findings include:

- A 2019 study shows that short telomeres are linked to an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

- A 2021 systematic review shows that shortening telomeres are associated with increased disease duration, lower brain volumes (as per MRI scans), and a higher degree of disability among patients with multiple sclerosis.

- A 2015 review shows that shorter telomeres significantly increase the risk of several psychiatric disorders.

- A 2021 study shows that not only are shorter telomeres linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, but in patients with coronary heart disease, they can also predict a higher risk of complications.

The results of earlier studies are consistent in linking shorter telomeres with chronic illness, neurodegenerative disorders, shorter longevity, and earlier death.

- DNA methylation

To understand what DNA methylation is, it is important to consider DNA as something dynamic and able to change. In particular, not all genes in the DNA are “expressed” at any given time. Some of your genes may be switched “off,” while others are “on” (or are expressed) due to internal or external factors.

For example, a certain gene that regulates inflammation in your body may have been functioning, or on, since your early days. Encountering chronic stress or adverse lifestyle changes later on in life can prompt the gene to shut down or turn off.

As a consequence, you may start to experience increased inflammation, which can make you suddenly more prone to frequent illness or even chronic diseases such as heart disease or diabetes.

The process used by the DNA to turn genes on or off is known as methylation. This biological process involves the addition of a methyl group (CH3) to the DNA molecule. This modification doesn’t change the DNA sequence itself, but it may switch genes on or off, in a process known as gene regulation.

Methylation patterns can change over time, and they are often influenced by age, lifestyle, environment, and disease state. It is estimated that the human genome contains 28 million methylation sites in the DNA, several of which change with age – making the DNA methylation rate an accurate predictor of biological age.

As we age, variations in DNA methylation become more frequent: the rate at which genes are regulated can increase in some areas of the body (e.g.: soft breast tissue, which has been seen to be as much as three years older compared to the rest of the body) while others decrease.

Connection to Health

Chronological age is commonly used as a risk factor to determine the level of risk for a range of diseases. For example, it’s widely accepted that adults aged 65 and older have a higher risk of diseases like cardiovascular disorders, diabetes, osteoarthritis, stroke, and cancer.

It is easy to see why chronological age is used in determining disease risk instead of biological age: this figure is easily accessible to both patients and healthcare providers. For instance, when a patient turns 65, their doctor will encourage them to stick to routine screening tests and take preventative measures.

However, there’s a caveat.

Let’s look at a patient who is chronologically 55, but has a biological age of 65. Their risk of disease is much higher than their chronological age would suggest.

As a result, they may not undergo screening tests or adopt lifestyle interventions that could modify their disease risk and protect them from complications. Left undetected, a higher biological age can make patients more prone to disease and disability as they age, which can kick-start a negative loop of chronic illness and add to the healthcare burden.

Over time, this can lead to a snowball effect: not implementing the right lifestyle interventions can increase the rate at which you are aging, which can exponentially increase your disease risk, ultimately affecting your longevity and lifespan.

It’s easier to think of biological age this way: your body doesn’t know how many birthdays you’ve celebrated, it only knows how well or badly your systems, organs, and tissues are aging internally. Consequently, it can act as the body of a younger or older person.

If you are biologically 10 years younger than your chronological age, your body is likely to match the health and disease risk profile of your biological age, not your chronological age. This can impact how long you’ll live and, more importantly, how many years you can live without disability or chronic illness.

Does Chronological Aging Intersect With Biological Aging?

Chronological age does not directly impact biological processes – rather, it gives us an indication of how old we are at any given point in life and what to expect from our health. For example, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, most breast cancer cases are diagnosed after the age of 50.

So, if you are approaching this milestone, you may wish to undergo screening tests for early detection.

Nonetheless, as we have seen above, your chronological age does not paint the full picture. For example, due to poor lifestyle choices and environmental factors, you may be aged 40, but have the same breast cancer risk level as a 50-year-old.

Chronological age intersects with biological age because, ultimately, as time passes, the state of our tissues, organs, and systems begins to decline. But the rate at which this happens is better outlined by biological age, which describes the rate of cellular retirement.

In turn, by halting cell division, cellular retirement determines how well the body’s tissue, organs, and systems function, and at what rate their function declines. Functional decline can affect the internal part of your body – such as organs and tissues – but it can also manifest with visible signs, such as reduced energy and mobility, skin changes, and memory problems.

Do We Define Ourselves by Chronological or Biological Age?

Above, we’ve looked at the fact that chronological age is just a number, which doesn’t necessarily describe how well the body is doing internally. So, why do we let it define us?

There are several reasons for this:

- Mindset

Our mindset plays a vital role in helping us control the rate at which we age. When we have a positive mindset, we are able to find purpose in life and stick to healthy lifestyle choices. For example, if you feel more energized and determined to stay healthy, you will find it easier to exercise regularly, eat healthy meals, and socialize.

On the other hand, if you are plagued by chronic illnesses and declining mental health, you are more likely to experience depression, social isolation, a sedentary life, and diseases like diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disorders – which further aggravate the picture.

Our mindset can also be influenced by our assumptions. Some people get ill just after celebrating their 60th birthday, simply because they now believe they are “old.”

Similarly, if you are in your 60s or 70s, experience declining health, and see yourself as old, you are more likely to think “I’m getting old, my health can only get worse – so, why try?” Think of this as a self-fulfilling prophecy.

These are boundaries that we set in place and dare not cross. But they are just that: self-limitations. Research confirms that even simply thinking that you are young and can improve your health can have a profound impact on your life.

In a 1979 study by Ellen Langer – known as the “Counterclockwise” experiment – a group of older adults was asked to spend five days in a retreat and live as if they were 20 years younger.

The results? Better hearing, memory, grip strength, vision, joint flexibility, manual dexterity, IQ, gait, and posture. The participants also experienced lower arthritis pain levels and appeared significantly younger after the retreat.

- Ageism and societal views

Besides our own mindset, external factors such as societal views and stereotypes associated with aging can also cause us to define ourselves by our age. Ageism can negatively impact a person’s quality of life, self-esteem, and health outcomes.

In practice, when people are perceived as old, they begin to act as old. They may begin to rely more and more on caretakers and cultivate feelings of hopelessness. This can cause them to take actions such as going into retirement or interrupting hobbies, which, in turn, inhibits their productivity, contribution to society, life purpose, social life, and mental and physical health.

Not only does this place excessive strain on a person’s well-being, but it can also contribute to the burden placed on their families, healthcare system, and pension scheme.

Why Is Knowing Your Biological Age Important?

Knowing what your biological age is compared to your chronological age can help you plan interventions and lifestyle modifications to ultimately improve your disease risk profile, increase longevity and healthspan, and boost overall wellness.

Knowing that you can modify your biological age is also important to rebuild your mindset and prevent your chronological age from defining you.

Early Detection Of Health Risks

Understanding your biological age provides invaluable health insights – it can work as a barometer that indicates your susceptibility to diseases before symptoms appear.

Knowing your level of risk can help you seek early intervention and medical advice, reducing the severity or even preventing conditions commonly related to age, from dementia to diabetes. By tackling your risk of disease early on, you can extend your healthspan and longevity.

Targeted Anti-Aging Strategies

Consider your biological age as a starting point to seek effective anti-aging interventions that will, in time, help you control your biological age and rate of aging. The goals of these strategies are to:

- Increase telomere length or reduce the rate at which they are shortening

- Support DNA methylation

- Support the healing and regeneration of damaged cells and tissues

- Boost the body’s ability to heal naturally

- Improve mental and physical health

Quantifiable Progress Tracking

Tracking your biological age offers objective measurements of health progress – more so than just tracking your chronological age. This data can help you better understand how different lifestyle modifications, medications, interventions, or therapies impact your health.

Therefore, it helps to make informed decisions and adjustments, leading to better, more sustainable health outcomes.

Can Aging be Reversed?

Above, you’ve learned that biological age can be modified. With the right interventions, you can not only slow down the rate of aging but also reverse it.

Although these interventions should be planned by a specialist around your unique goals and needs, some key anti-aging strategies include:

- Exercise. Not only does exercise help improve physical strength, flexibility, pulmonary capacity, and cardiovascular health, but it has also been seen to help preserve telomere length as we age.

- Nutrition. Eating a Mediterranean diet has been seen to be the optimal choice to support telomere length and reduce mortality from age-related diseases. This is because it is rich in legumes, nuts, fruits, vegetables, mostly unrefined grains, and a high intake of unsaturated lipids (e.g.: olive oil). Oppositely, alcohol, red meat, or processed meat have been associated with telomere shortening.

- Sleep. A 2023 review of 22 studies shows a clear link between good sleep quality and duration and optimal telomere length.

- Stress management. A review published in 2022 shows that chronic psychological stress is a major contributor to aging. Stress is also linked to a range of age-related diseases, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, autoimmune diseases, and depression.

- Environmental adjustments. Environmental contributors can impact aging in multiple ways. A stressful environment can lead to chronic stress and impact sleep and nutrition. Furthermore, in vitro clinical trials have shown that significant alterations take place in the length of the telomeres after exposure to pollutants and toxins.

- Anti-aging treatments. Anti-aging treatments span from caloric restriction to nutraceuticals and hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Certain stem cell and platelet-rich plasma therapies may also help replenish the reserves of stem cells and growth factors in aging adults, to support the ability of the body to heal naturally. These interventions can help re-establish balance in bodily systems affected by aging.

- Supplements. Supplements such as those combined in the RELATYV formula – including NAD+, curcumin, resveratrol, glutathione, and NAC – can offer important anti-aging properties.

For example, NAD+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) plays a critical role in energy metabolism and the reduction of oxidative stress. Polyphenol like resveratrol can help reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases, while collagen provides support, elasticity, and strength to tissues and organs.

Ultimately, getting to know and monitoring your biological age can help you make better-informed decisions about your health and allow you to extend the number of years lived – and the ones lived without disability and disease!

What RELATYV does is put you back in control. Starting with an accurate biological age test, you’ll be able to better understand how your body is aging. Your RELATYV age is a measure obtained by comparing your biological age to your chronological age. This figure combines the best of both worlds: just like chronological age, it is very easy to quantify – but it is also as accurate and modifiable as your biological age.

The RELATYV platform can calculate your RELATYV age using an advanced algorithm, which elaborates critical health data – from your medical records to performance indicators. Equipped with this knowledge, you’ll be able to start planning and introducing anti-aging interventions guided by a team of specialists.

As you implement custom interventions and recommendations for longevity and wellness, you can monitor changes in your biological age, thus reducing your disease profile risk and increasing your healthspan.

Slow Down The Ticking Clock With Us

Too often, we let our chronological age define us, our achievements, our health, and our productivity. But the adage “age is just a number” could not be more true when we are talking about chronological age.

Instead of surrendering to an aging mind and body, you can now take control of your health – starting by understanding what your biological age is. Monitoring this figure and taking steps to reduce your biological age can help you feel younger and act younger, while also reducing the risk of disability and boosting your longevity.

Age: Why Knowing The Difference Matters

Biological Age vs. Chronological Age

RACIAL DISPARITIES IN BIOLOGICAL vs. CHRONOLOGICAL AGE New Study Cites Implications for Patients, Providers, and PolicymakersBecause of the damaging socioeconomic and psychosocial stressors they experience as a routine matter of daily life, the health and biomechanical systems of African American bodies "weather" or deteriorate faster than those of white people. A new study of the molecular and physiological data from 20,000 older Americans finds that the bodies of Black people are, on average, biologically nine years older than the bodies of white people of the same chronological age.

Entitled "Patterns and Life Course Determinants of Black-White Disparities in Biological Age Acceleration: A Decomposition Analysis" and published in the Journal Demography, the study was among the first to directly link multiple biomarkers to specific social determinants of health to quantify their contribution to Black/White disparities in accelerated aging.

Essentially, the study documented the way that the social determinants of health directly affect the function and viability of certain human body organs and systems in ways that cause Black people's bodies to deteriorate faster than white people's bodies, thus fostering higher risks and vulnerabilities for premature illness and death.

Headed by LDI Senior Fellow Courtney Boen, PhD, MPH, a faculty member at Penn's School of Arts and Sciences, the team of researchers from five universities writes:

"Black health patterns are 'first and worst': Black people experience earlier onset of health decline, greater severity of disease, and poorer survival rates than Whites. Racism patterns exposure to many damaging social exposures linked to accelerated aging... Relative to White people, Black people in the United States live shorter, sicker lives."

Using three blood chemistry-based measures of biological aging the researchers quantified the progress of age-related deterioration across multiple bodily systems and examined how chronic exposures to socioeconomic and psychosocial stress contributed to different racial patterns of biological aging and age-related biophysical deterioration for Blacks and whites.

"Racism contributes to population health inequality partly by differentially exposing those racialized as White and those racialized as Black to disparate material, psychosocial, and environmental opportunities and risks across the life span generating divergent age patterns of physiological dysregulation and biological aging and contributing to the racial patterning of morbidity and mortality risk."

"Dysregulation" describes disruptions to a body's ability to balance and maintain a stable internal environment that is crucial for optimal organ and cellular functioning and survival. When vital systems become dysregulated, they lose their ability to control and self-regulate themselves, causing or worsening various morbid conditions.

READ THE STUDY: https://read.dukeupress.edu/demograph...

No comments:

Post a Comment