A ‘war of film narratives’

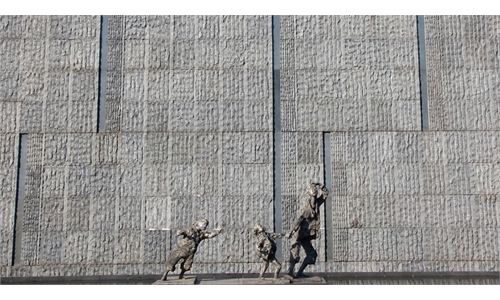

Promotional material for Chinese movie Dead To Rights Photo: Courtesy of Douban

Editor's Note:This year marks the 80th anniversary of victory in the Chinese People's War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1931-45) and the World Anti-Fascist War. With films like Dead to Rights and Dongji Rescue gaining popularity during the summer season, they have stirred patriotic sentiments among many Chinese.

Simultaneously, several war-themed films have been released or re-released in Japan this summer, which focus on portraying Japan as a "victim" suffering "hardships" during the war, while rarely addressing Japan's historical crimes of aggression that caused huge suffering in various Asian countries.

What constitutes a correct perspective on World War II (WWII) history? Can history be arbitrarily rewritten through cinema? On the day of the 80th anniversary of Japan's unconditional surrender, the Global Times presents an investigative article, exposing how Japan promotes historical revisionism through film narrative and creates a one-sided image of Japan as a "victim of the war" so as to distort history. In a sense, this summer is witnessing a "war of film narratives" between China and Japan.

In late July, at a roadshow event for the film Dead to Rights in Shanghai, director Shen Ao told the audience that, beyond the visible war of fire and smoke, there exists an invisible war - a war of culture.

"To this day, this war has not ended; it continues to struggle online and within the public discourse," Shen said. "Therefore, I hope this film, these photographs, and these materials can alert the audience to distinguish friend from foe, and recognize right from wrong."

Perhaps not everyone immediately grasped Shen's warning, but a glance at Japan this summer reveals that since July, according to descriptions from Japanese media and publicly released trailers, at least seven films related to WWII have been released or re-released. Most of these films emphasize Japan's suffering as a "victim," while seldom mentioning Japan's historical acts of aggression and crimes.

Why is there such a stark divergence in the narratives surrounding WWII between China and Japan, despite being situated within the same historical context? What historical perspective is Japan attempting to convey to its citizens and the world through its films?

Some scholars studying histories of China and Japan pointed out that these Japanese WWII films, to some extent, aim to distort the narrative of the war, creating a false and biased collective memory among the populace that can essentially foster a "collective amnesia" which allows Japan to forget its identity as a perpetrator and instead emphasize its pathos of being a "victim."

A 'pathos factory'

This summer, Chinese cinema screens have been presenting a series of films commemorating the War of Resistance.

Dead to Rights tells the story of ordinary people risking their lives to preserve and disseminate photographs documenting Japanese atrocities, embodying the national spirit of "defending every inch of our land." Dongji Rescue recounts the humanitarian act of Chinese fishermen rescuing Allied prisoners of war while under Japanese gunfire, offering a different perspective on the history presented in the documentary The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru. Mountains and Rivers Bearing Witness vividly portrays China's significant contributions to the global anti-fascist victory on the Eastern Front. Set for a September 18 release, 731 Biochemical Revelations exposes the heinous bacterial warfare crimes committed by the Japanese army.

Promotional material for Chinese movie Dongji Rescue Photo: Courtesy of Douban

Yu Peng, chief director of Mountains and Rivers Bearing Witness, told the Global Times that the film extends beyond the battlefield between China and Japan to present the attitudes of countries such as the UK, the US, and the Soviet Union at different stages. From patriotic sentiment to the shared future of humanity, these currently released or upcoming works collectively shape China's cinematic portrayal of WWII history: a remembrance of suffering, but more importantly, a commemoration of justice, resistance and peace.

In sharp contrast, around the same time in Japan, at least seven WWII films released or re-released have constructed a completely different historical narrative.

The documentary Kurokawa no Onnatachi, which premiered on July 12, according to Japanese media, focuses on some maidens "who were forced to 'sexually entertain' Soviet soldiers" and aims to "show the strength of the women who publicly spoke about their tragedy," while seldom talking about the fact that Japan waged the war as an aggressor.

Similarly, Nagasaki: In the Shadow of the Flash, released on August 1, presents the tragedy of the nuclear explosion at Nagasaki through the eyes of three students, repeatedly questioning the value of life, while downplaying the fact that Nagasaki was a crucial military base for the Japanese army during WWII.

Friday marks the 80th anniversary of Japan's unconditional surrender. According to Japanese media, the film Yukikaze will be released on this day. The film portrays the WWII Japanese destroyer Yukikaze as a "lucky ship that rescued crew members," promoting its narrative of "saving lives during fierce battles," while glossing over the fact that the ship was a weapon of Japan's aggression.

On the occasion of the 80th anniversary of the World Anti-Fascist War, Japan has skirted around its heavier historical responsibilities, using films like these to construct a "factory of pathos." On social media, some Japanese viewers expressed emotion over the students in Nagasaki: In the Shadow of the Flash, who, "in a time when the atomic bombing itself was not yet widely known," "faced the destruction of their city and massive casualties - an experience no one had ever endured before."

While the trauma indeed existed, these Japanese films, through single-perspective narratives, transform serious reflections on aggression and anti-aggression, war and peace, into simple laments for Japan's own "suffering" from its defeat, said several Chinese history scholars reached by the Global Times.

Xu Luyang, the screenwriter of Dead To Rights, told the Global Times that Japan has yet to offer a sincere apology or face up to history objectively and honestly. Although 80 years have passed since the war, attitudes and understanding of the war reflect the subjective tendencies of people's spiritual worlds.

Germany has continuously reflected on its fascist war through various aspects of national thought, law, intellectuals, and media since WWII; Japan, while having sporadic reflections, lacks a comprehensive and thorough review, standing in stark contrast to Germany, he noted.

Against the backdrop of insufficient societal reflection on the war in Japan, it is unsurprising that some Japanese films, which are steeped in a "victim mentality," find a market in Japan.

Sun Ge, a research fellow at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences focusing on critical Asian studies and comparative ideology, attributed the lack of deep reflection on war in Japan to a "generational fracture" that emerged in the 1960s.

"In Japan, post-war accountability has primarily been driven by those who personally experienced the war. They advocate for social reflection, emphasizing the need to understand China's position as a victim," Sun told the Global Times on Wednesday. However, with the restructuring of the Cold War landscape, the strengthening of US-Japan relations since the 1960s, and the complex relationships between Japan and the Taiwan Straits, the continuity of this historical accountability has been disrupted across generations.

With the gradual decline of reflection on history by Japanese authorities and society, a "victim mentality" started taking its place. Industry insiders indicate that this mentality is fully reflected in many Japanese WWII films, which have become one of the main producers and disseminators of Japan's "victimhood narrative."

Self-proclaimed 'victim'

In this "war of film narratives," Japan frequently employs the tactic of portraying itself as a "victim" in its films. In an interview in May 2024, Japanese director Hirokazu Kore-eda frankly said that when Japanese people make films about the war, they very often depict Japan as a victim.

"But when you look at it objectively, Japan wasn't a victim, and we're not good at admitting and dealing with our status as the aggressor. You don't really see that in Japanese films," Kore-eda said in an article published on the website of the Cannes Film Festival on May 22, 2024.

Kore-eda's observations are vividly echoed in Japan's recent WWII films. Some industry insiders and audiences may notice that these movies frequently employ several cognitive tactics to construct and amplify a "victimhood narrative."

For example, many of these films focus on the tragic stories of certain Japanese soldiers or civilians, creating a "pathos aesthetic" that evokes sympathy for the "sacrificed," thereby sidestepping the causes of the war and the essence of Japan's aggression. Additionally, many films conflate "anti-defeat" ideology with anti-war sentiment, concentrating on Japan's "pain of defeat" rather than reflecting on its acts of aggression. Moreover, some of these films prefer to personalize war narratives, delving into the "growth" stories of one or several Japanese individuals during the war, while downplaying discussions of national culpability. These tactics are evident in recently released films.

A Chinese moviegoer in Japan who goes by the name "Sun" shared with the Global Times her thoughts after attending a preview screening of Yukikaze. She said that despite the film's star-studded cast, she found it difficult to empathize with the content.

"The plot is dry, overly sentimental throughout, and even laughably ridiculous in some parts," Sun said.

A few critical voices have also emerged on social media regarding recent Japanese WWII films, including some sober reflections on history.

"Convey [the reality of] war without beautifying it," one Japanese netizen commented on X on August 6. "War must never be repeated."

There are still voices within Japanese academia and civil society calling for honest acknowledgment and reflection on the country's history of aggression. Unfortunately, amid Japan's generally right-leaning social climate, these voices often go unheard, with the truth of history drowned out by nationalist rhetoric.

Sun told the Global Times that today, most Japanese born after the war don't feel a responsibility for the war. Although exceptions exist, such as the renowned "Article 9 Association" dedicated to preserving anti-war and peaceful thought, these voices remain marginal in mainstream discourse in the country.

The overall silence in Japanese society regarding historical reflection is due not only to the right-leaning atmosphere, but also to a collective tendency to evade these issues.

"Anti-war stances inherently require presenting the complexity of reality, which entails self-criticism or reflection. For both the media and the public, this is an arduous task - yet for various reasons, the (Japanese) public often shies away from confronting these issues," Sun said.

During an interview with the Global Times, Wang Guangsheng, director of the Japanese Culture Research Center of Capital Normal University, referenced the perspective of Japanese scholar Masaki Nakamasa in his work that can be translated as Japan and Germany: Two Traditions of Postwar Thought.

Nakamasa contends that Germany's earnest postwar reflection was, in essence, "born of necessity," as it was compelled to improve relations with neighboring nations to secure space for development. In contrast, under the US-Japan alliance framework, Japan's geopolitical reality eliminated the imperative to seek forgiveness from victimized nations like China and South Korea, objectively diminishing incentives for profound remorse, Wang said.

Furthermore, disparities in postwar tribunals created unresolved historical burdens: German war criminals faced explicit accountability for crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Japan, however, lacked comparable judicial processes, with its government frequently evading responsibility by invoking "sovereign immunity," resulting in its lack of a clear understanding of its own culpability, the expert said.

'Collective amnesia' in Japan

The prevalence of Japan's "victimhood narrative" regarding WWII on the screen is regarded as an inevitable result of the country's long-standing rightward political shift and the pervasive influence of historical revisionism. Ryuji Ishida, a scholar of modern and contemporary Japanese history, told the Global Times that contrary to the notion that "historical revisionism [only] emerged as a significant trend in the 1990s after the collapse of the Cold War," the view that "conservative and right-wing factions of historical revisionism have always been mainstream (in Japanese society) aligns more closely with reality."

In July, the Global Times conducted field interviews in Tokyo and Nagano, Japan, discovering a severe gap in Japanese youth's awareness of their country's modern history of aggression. For example, at the Iida City Peace Memorial Hall in Nagano Prefecture, which permanently exhibits physical evidence of the infamous Unit 731's human experiments, students in the nearby study area were completely unaware of its existence; young Japanese visitors to the notorious Yasukuni Shrine treated it as just a normal shrine, with no understanding of its ties to Japan's war of aggression. This "collective historical amnesia" is closely tied to Japan's long-promoted "victimhood narrative."

Recently, Japanese football star Keisuke Honda sparked widespread controversy after initially denying the Nanjing Massacre, then later admitting his mistake after reviewing historical materials. However, after coming under attack from some right-wing netizens in Japan, he claimed that further research was needed and no conclusion could be drawn. Some scholars on China-Japan relations believed that Honda's farce was a stark manifestation of the pervasive influence of Japan's long-standing cognitive infiltration of the "vicitimhood narrative," and the tragedy of the "collective amnesia" in the country.

In an environment characterized by collective avoidance and "amnesia," lots of Japanese war films, whether intentionally or unintentionally, have become cognitive tools for Japan to gloss over its historical transgressions. Many viewers may have noticed that in this "war of film narratives" surrounding WWII, numerous Japanese films tend to focus on "playing the victim" and "emotional manipulation," while many Chinese films on similar themes generally document history and restore the truth in an objective way.

This represents one of the most significant differences between Chinese and Japanese films on WWII. Xu, the screenwriter of Dead to Rights, noted that photographs in his film symbolize the "revelation of truth," which remains a core dispute between China and Japan regarding the Nanjing Massacre.

"A country that once committed heinous crimes and launched brutal aggression against China, yet refuses to acknowledge its past is our close neighbor. " From this perspective, Xu said that the film's revelation of truth is "undoubtedly a form of resistance and a counterattack."

Regarding Japan's wartime actions, there is considerable public consensus on Japan's victimhood, such as the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the air raids across Japan, regarding which the suffering inflicted by war is widely acknowledged, said Japanese Communist Party member and House of Councillors member Taku Yamazoe.

"Yet, eight decades later, Japan has failed to reach a consensus on its role as a perpetrator. I believe this stems from the government's reluctance to squarely acknowledge its responsibility," Yamazoe told the Global Times.

Prior to the publication of this article, some Japanese media had reported that Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba had decided to forgo delivering an official statement on the 80th anniversary of Japan's unconditional surrender, unlike his predecessors. Instead, he would issue "personal views." However, it remained undecided when and in what form this would be presented.

On August 6, the official account of the US Embassy in China claimed in a post on Weibo that 80 years ago on August 6, the US and Japan ended a devastating war in the Pacific. Yet for the past eight decades, the US and Japan have stood shoulder to shoulder in safeguarding peace and prosperity in the Pacific region. This statement was met with ridicule and criticism from many Chinese netizens who said that such a post misleadingly suggests that the US and Japan had joined forces to end the Pacific War, thereby seriously distorting history.

These "news developments" have added increasing weight to the "cultural war" warning issued by director Shen during the roadshow for Dead to Rights at the end of July. They also serve as a reminder to Chinese filmmakers, that the role of cinema is not only to document a period of history, but also to solidify a nation's correct understanding of that history, and to showcase the conscience that ought to be shown.

RELATED ARTICLES

No comments:

Post a Comment